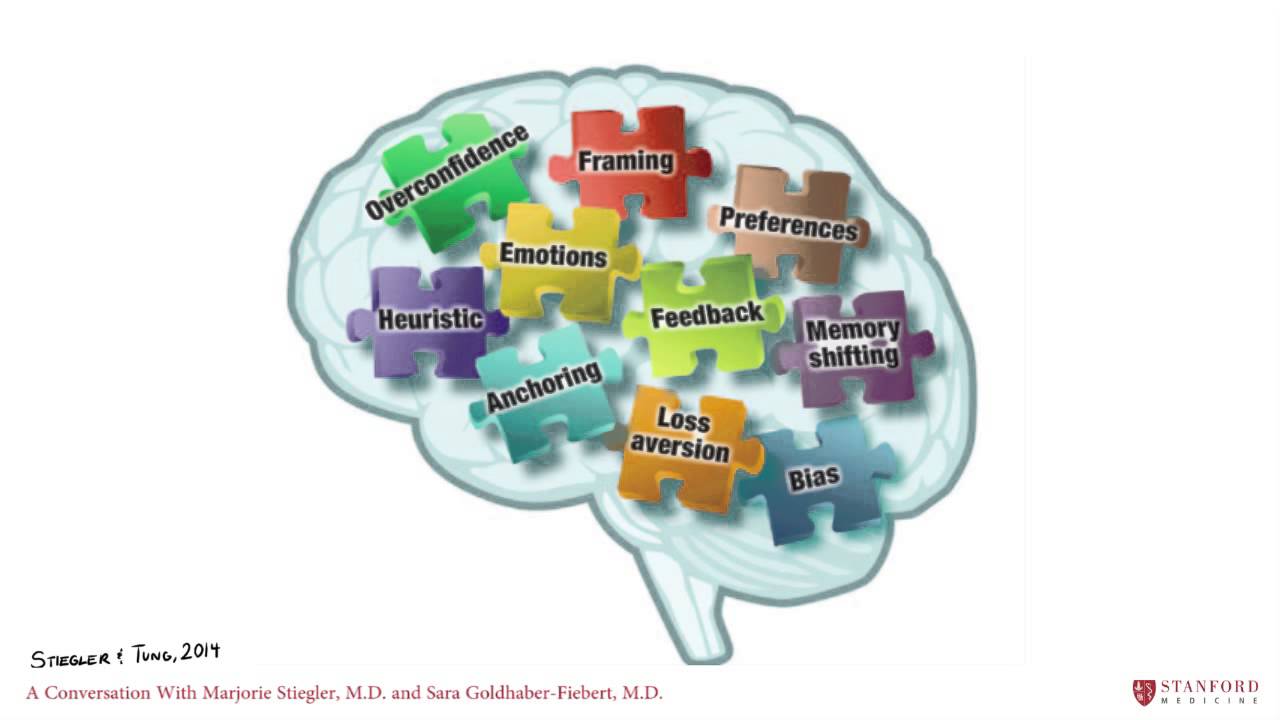

Decision making errors in medicine are common. Why do doctors make diagnostic error? Can cognitive errors - which are caused by cognitive bias, memory distortions, heuristics, and emotions - be prevented? The behavioral psychology of decision making applies in medicine just as in daily life. Medical heuristics are often useful, and cognitive decision errors are often invisible. This video is an introduction to the contribution of cognitive errors to medical mistakes. Additional material can be found along with the video file in the peer-reviewed educational repository of the Association of American Medical Colleges here: Stiegler M, Goldhaber-Fiebert S. Understanding and Preventing Cognitive Errors in Healthcare. MedEdPORTAL Publications; 2014. Available from: [ Ссылка ] [ Ссылка ]

Consider these ideas: In medicine, experience is largely based on chance. – clinicians learn based upon patients and their ailments that so happen to come into the clinic or the ER or the OR. Each clinical encounter is added to a mental catalog of cases, and the sum of these cases (or at least, what we can recall about them) is our experience. We try to balance this with semantic memory (facts).

Even if we can count on chance (or increasingly in medical education, simulation) to ensure we have a full mental catalog of cases, it is worth taking a moment to understand how memory works. Let’s consider availability bias and memory reconstruction errors.

Availability Bias

The readiness with which a case from our catalog comes to mind is often unrelated to the probability of it occurring now or in the future.

Memory Reconstruction

Memories are not captured literally like words in a book that can simply be referenced by opening to the proper page. Instead, we store and recollect event by gist, making them shorter and more sometimes more coherent than the actual event. Applying this concept to medical experience, experts have large collections of schemas or “illness scripts” that guide recall of stereotyped versions of experiences. These scripts allows experts to almost immediately recognize patterns and the presence of all or nearly all data pieces that fit the script. With increasing experience, particularly for experts diagnosing routine cases, ‘‘reasoning through’’ a case plays only a small role (if any).

When we consider how memory works, it becomes apparent that very same experiences that become an expert’s library of illness scripts – and often lead to immediate and accurate recognition of medical situations – can lead those same experts astray. Scripts lead to semi-‐automatic thinking, which lead to reduced consideration of alternative options. This “premature closure” of diagnostic consideration – selecting the first and most “obvious” choice – leads to error when the true diagnosis is not common or is atypical.

![Интересная физика 1 [Эффект Безызносности, Доплера, Мпембы, Баушингера, электропластический эффект]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/hi-OiqeGXNU/mqdefault.jpg)