Giovanni Gabrieli (c. 1554/1557 – 12 August 1612)

In the waning years of the Renaissance, northern Italy emerged as an epicenter of musical breakthroughs. While Rome hewed to sublime, classic counterpoint—a stabilizing influence, as the conservative Vatican saw it—proud and powerful Venice, at the northern tip of the Adriatic, grew ever more audacious in its musical experiments. Musicians from all the northern Italian cities and from foreign lands aspired to appointments there, and the Doges supported their musical enterprises lavishly, nowhere more exorbitantly than at the Basilica of San Marco.

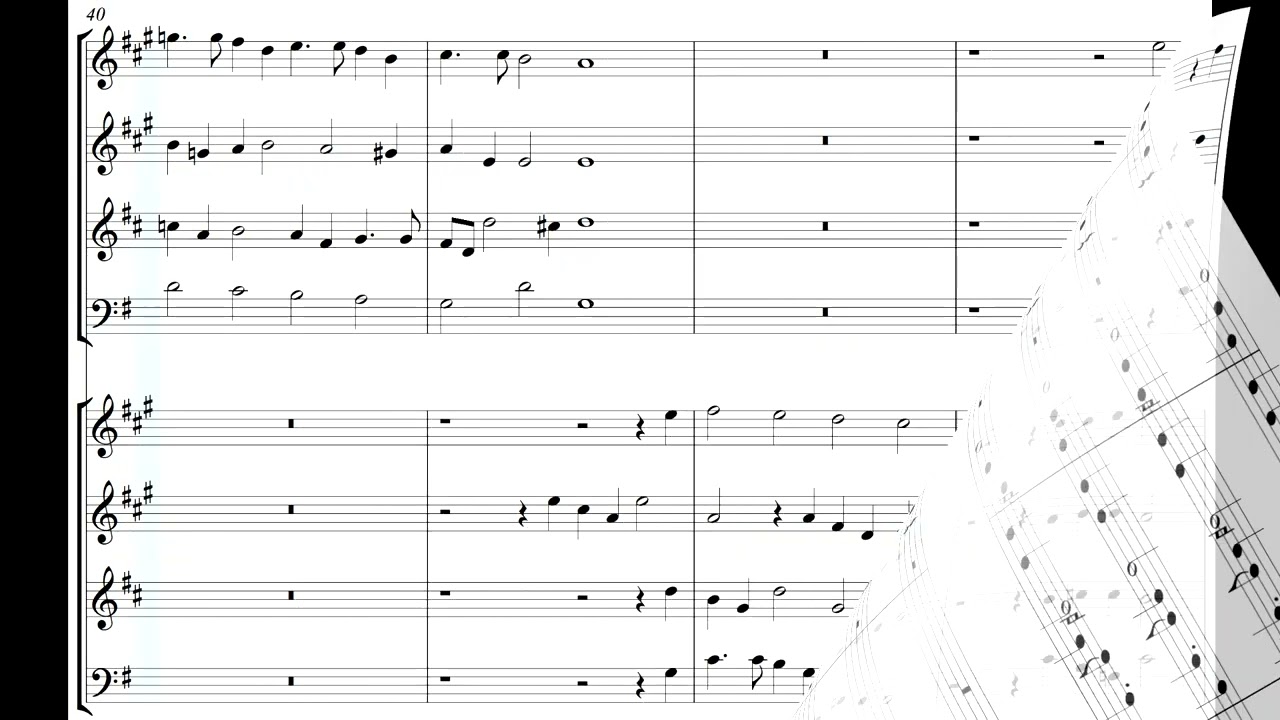

Some of the other churches of Venice—where notable churches stand on nearly every square—echoed San Marco’s enthusiasm for lavish music, though none exceeded it. One of San Marco’s defining characteristics was architecture that supported the separation of the performers into discrete units that could be stationed in various balconies around the church. These cori spezzati (“spaced-out choirs” might serve as a jocular translation) gave rise to a repertory of polychoral vocal and instrumental music that has rarely been matched for sheer splendor.

Giovanni Gabrieli proved especially adept with instrumental writing of this sort. Schooled by his uncle Andrea Gabrieli and enriched by work and study with Orlando di Lasso at the Bavarian court in Munich from 1575 to 1579 (during which he fortunately avoided a plague that devastated Venice), the composer returned to his native city in 1584. In a surprise move, the reigning organist of San Marco, Claudio Merulo, resigned his post to move to Parma (a step down, in terms of prestige); and at an open competition for his successor, held on New Year’s Day of 1585, Gabrieli was unanimously accepted to join the basilica’s staff as deputy to his uncle, who ascended to the principal organist’s post. A month later Gabrieli assumed a concurrent position as organist at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, which became second only to San Marco as a hotbed of sumptuous music making. From then until 1612, when he died of a kidney stone and was buried in the parish church of San Stefano, Gabrieli composed prolifically, leaving a legacy of motets, madrigals, organ works, canzonas, and sonatas. In fact, he appears to have been the first composer to employ the term “sonata,” which he used in a generalized way to describe instrumental works that didn’t adhere to any other established form. Canzon septimi toni à 8 and Sonata pian’ e forte were published as part of the Sacrae symphoniae collection of 1597. (A second collection was published in 1615.) The septimi toni of the first work refers to the mode or scale on which the piece is based. Sonata pian' e forte—as its title suggests—utilizes dramatic dynamic contrasts.

—James M. Keller

James M. Keller is Program Annotator of the San Francisco Symphony and New York Philharmonic. His book Chamber Music: A Listener’s Guide, published in 2011 by Oxford University Press, is also available as an e-book and an Oxford paperback.

Giovanni Gabrieli composed his Canzon septimi toni for the majestic St. Mark's Cathedral in Venice, where he was organist and principal composer from 1585 until his death. Gabrieli came from a musical family - he succeeded his uncle Andrea as principal composer at St. Mark's and edited many of the latter's works for publication. After Gabrieli's father died in 1572, when Giovanni was a teenager (the year of his birth is unknown, but speculation places it between 1554 and 1557), uncle Andrea was likely his guardian and teacher.

The Canzon comes from a collection of music for brass that Gabrieli composed for church use and published in 1597 under the title Sacrae symphoniae. This was the first collection devoted exclusively to Gabrieli's works, and it reflects his experience as a church musician. The pieces in the collection are for various combinations of trumpets and trombones, whose players would have been placed antiphonally inside St. Mark's to take advantage of the church's acoustics and to clarify the dialogic musical structure of works such as the Canzon. The Canzon septimi toni (so-called because it is written in the Mixolydian church mode, which is based on G, the "seventh tone") shows Gabrieli developing musical material in dialogue between instrumental groups. The spatial arrangement of the various instruments is necessitated by the score's antiphony, with the instruments answering each other from all sides of the performance space, enveloping the listeners in a late 16th-century version of surround sound, an effect recreated here by having the musicians play from different parts of the auditorium.

- John Magnum is the Los Angeles Philharmonic's Program Designer/Annotator

![SOOJIN MONA LISA [ПЕРЕВОД НА РУССКИЙ/КИРИЛЛИЗАЦИЯ Color Coded Lyrics]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/s6hnmByFJTQ/mqdefault.jpg)