Unprecedented observations of a nova outburst in 2018 by a trio of satellites, including NASA’s Fermi and NuSTAR space telescopes, have captured the first direct evidence that most of the explosion’s visible light arose from shock waves — abrupt changes of pressure and temperature formed in the explosion debris.

A nova is a sudden, short-lived brightening of an otherwise inconspicuous star. It occurs when a stream of hydrogen from a companion star flows onto the surface of a white dwarf, a compact stellar cinder not much larger than Earth.

The 2018 outburst originated from a star system later dubbed V906 Carinae, which lies about 13,000 light-years away in the constellation Carina. Over time — perhaps tens of thousands of years for a so-called classical nova like V906 Carinae — the white dwarf’s deepening hydrogen layer reaches critical temperatures and pressures. It then erupts in a runaway reaction that blows off all of the accumulated material.

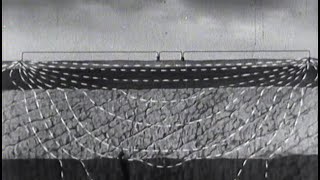

Fermi detected its first nova in 2010 and has observed 14 to date. Gamma rays the highest-energy form of light require processes that accelerate subatomic particles to extreme energies, which happens in shock waves. When these particles interact with each other and with other matter, they produce gamma rays. Because the gamma rays appear at about the same time as a nova's peak in visible light, astronomers concluded that shock waves play a more fundamental role in the explosion and its aftermath.

The Fermi and BRITE data show flares in both wavelengths at about the same time, so they must share the same source shock waves in the fast-moving debris.

Observations of one flare using NASA’s NuSTAR space telescope showed a much lower level of X-rays compared to the higher-energy Fermi data, likely because the nova ejecta absorbed most of the X-rays. High-energy light from the shock waves was repeatedly absorbed and reradiated at lower energies within the nova debris, ultimately only escaping at visible wavelengths.

Astronomers have proposed shock waves as a way to explain the power radiated by various kinds of short-lived events, such as stellar mergers, supernovae — the much bigger blasts associated with the destruction of stars — and tidal disruption events, where black holes shred passing stars. Further studies of nearby novae will serve as laboratories for better understanding the roles shock waves play in other more powerful and more distant events.

Read More: [ Ссылка ]

Music Credit: "Scientist" from Universal Production Music

Video Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Chris Smith (USRA): Lead Animator

Chris Smith (USRA): Producer

Scott Wiessinger (USRA): Producer

Francis Reddy (University of Maryland College Park): Lead Science Writer

Scott Wiessinger (USRA): Narrator

Scott Wiessinger (USRA): Editor

This video is public domain and along with other supporting visualizations can be downloaded from NASA Goddard's Scientific Visualization Studio at: [ Ссылка ]

If you liked this video, subscribe to the NASA Goddard YouTube channel: [ Ссылка ]

Follow NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

· Instagram [ Ссылка ] · Twitter [ Ссылка ]

· Twitter [ Ссылка ]

· Facebook: [ Ссылка ] · Flickr [ Ссылка ]

![Как работает Графика в Видеоиграх? [Branch Education на русском]](https://s2.save4k.org/pic/_j8R5vlA0ug/mqdefault.jpg)